|

Ros

Davies' Co.

Down, Ireland Genealogy Research Site

© Rosalind Davies 2008 Permission granted to reprint research for non-profit use only |

Shipping Tragedy April 1937

by Leslie Campbell

Loss of SS Alder & SS

Lady Cavan in Carlingford Lough &

drowning of Capt. Robert Campbell & wife Kate

Use

the Find button in your Edit tab to search for individuals.

Contents:

|

|

|

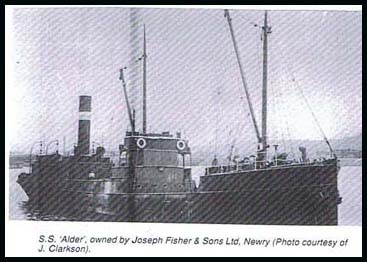

The ALDER;

SHIPPING DISASTER

IN CARLINGFORD LOUGH SUNDAY 4th APRIL

1937

At 4a.m. on 4 April 1937, Fishers’ steamer the Alder (341 tons) edged her way into the Lough in dense fog,

steam whistle sounding sonorously. Unwilling to proceed through Narrow Water,

Captain Robert Campbell, dropped anchor off Greencastle, which is on the Down

side of Carlingford Lough, opposite Greenore on the Louth side and a short

distance north of Kilkeel. It was the intention of Captain Campbell to lie

up for a few hours before making for Newry.

|

|

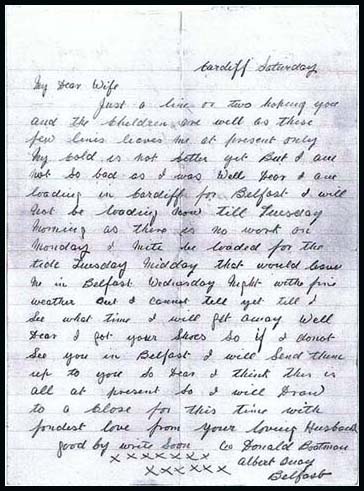

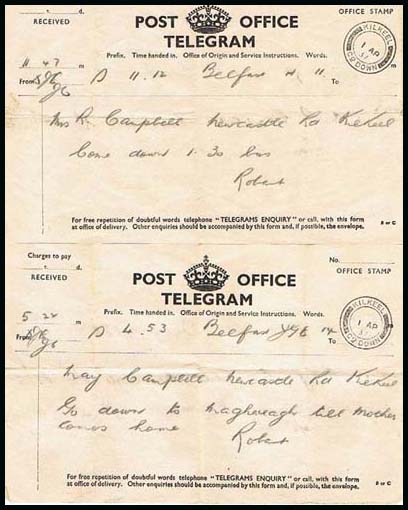

Aboard the Alder were Captain Robert

Campbell (42) and his wife Kate

(39) and the crew: Chief Engineer Robert

McGrath married with four children, of 3 Erskine Street,

Newry; Second Engineer J. Davis(47) married

with three daughters, of 41 Kingscourt Street, Belfast; Mate Michael

O’Neill of Fathom, Newry; Deck Hands - Jack

Gorman of Rooney’s Terrace, Newry; John

Conlon married with four children, of Upper Chapel

Street, Newry; James

Hollywood of Fathom, Newry and W.

Cahoun of Carrickfergus. The Alder was anchored for less than a quarter of an hour when the

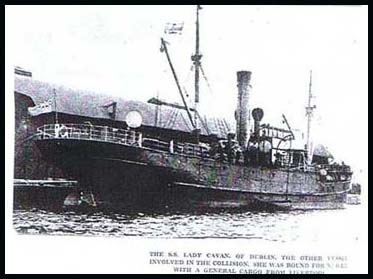

Lady Cavan (602 tons), under the control of Captain Gallimore

and carrying a general cargo from |

| Capt. Robert Campbell | Mrs. Catherine (Kate) Campbell | |

The crew of the Alder thought that there was no immediate danger

(although coal could be seen pouring through a rent in the plates) but the

captain and crew of the Lady Cavan realised the great danger that the

Alder and crew were in and offered assistance but those aboard the

Alder declined it again apparently minimising the danger.

Captain Campbell went below to arouse his wife Catherine and she came on deck with

him wearing an overcoat over her night attire.

The bow of the Lady Cavan was plunged into the collier in the collision

and when they were locked together there was a steadiness which concealed

the gravity of the injury the Alder had sustained, so that when the

Lady Cavan reversed engines and withdrew from the collier the vessel

suddenly developed a list.

|

|

The water rushed in through the yawning chasm caused by the impact and

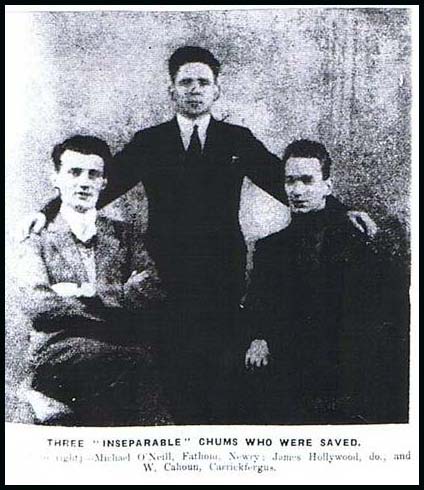

carried the Alder to the bottom of the Lough. All aboard the Alder went down into to the depths. O’Neill and Just after they had got on to the lifeboat they saw Cahoun, a non-swimmer,

come to the surface fortunately beside an oar which he held on to until

a lifeboat from the Lady Cavan rescued him. The Lady Cavan lifeboat circled around and searched until daylight

but there was no sign of Captain Campbell, his wife, who had

only at the last minute decided to accompany him on the voyage, or the

other four crew members. |

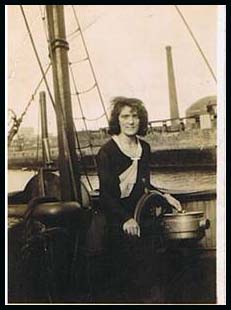

| John Conlon | L-R; Michael O'Neill, James Hollywood & W. Cahoun | |

The three rescued men M. O’Neill, J. Hollywood and J. Cahoun were

good friends and had only a few weeks previous been photographed together.

They were fed, clothed and sent home by the Shipwrecked Fishermen and Mariners’

Royal Benevolent Society.

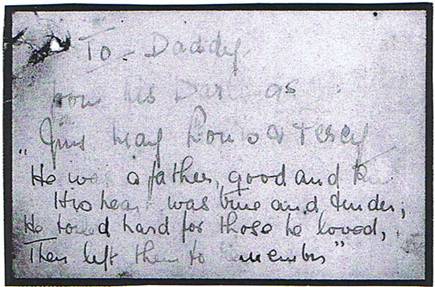

Captain Campbell and his wife had been married 17 years and left

four children: James (16), May (14), Louis (12) and Percy (9).

Mrs. Campbell had two sisters- Mrs. Nicholson and Mrs. Harper and one

brother Mr. Samuel Hale who is in

Captain Campbell was the son of Mr. and Mrs. James Campbell,

Maghereagh, Kilkeel and leaves four brothers; Messrs. Charles, William

John, James and Harry. It appears that Mrs. Campbell had arranged to be

home for dinner on Sunday. The children were stopping with their grandparents.

The mountains around the Lough still bore the traces of a recent heavy

snow and one can only imagine with a shudder how the six poor victims and the

three survivors must have felt in the icy waters of the Lough.

On the Sunday afternoon the Lady Cavan steamed up to Victoria

Locks, the entrance to the Newry canal. The vessel remained there for several

hours before going on to the Albert Basin, which she reached about 6 p.m. Groups

of people watched her sadly, in silence, for the tragedy affected everyone.

Like a funeral pall the black smoke hung over the green funnel as she steamed

past the pierhead.

The Sabbath stillness of the town seemed doubly intense as the dejected

townspeople gazed on the ship, gloomily conjecturing the feelings of those on

board her. Even the children stood wide-eyed and silent looking at her – and

beyond the town.

‘Under the dove-grey sky – as

wide as death-

The sea,

Fall, fall way, all soot and dust despair,

Turmoil and broil, uncertainties that rend,

All grinding noise and pain be ever still.

Here is the end-

Unmeasured sands to walk as spirits may

With washed unweighing feet, forever free.

The hush of waves, almost

unreachable

By mortal sense, as in Eternity’.

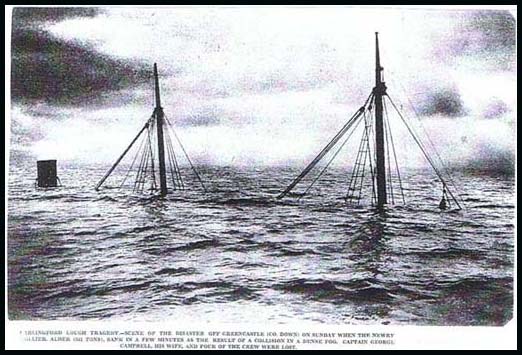

On Monday sightseers from various parts came to gaze at the scene of the

collision at Greencastle, but saw nothing more eventful than the operation of

shipping potato supplies from the Down to the Louth side of the Lough.

A thick mist hung over the Lough like a pall of death. A few hundred yards

from the shore the mast tops of the ill-fated Alder mournfully projected

over the waves and the peace of death was all-pervading. The visitors included

some of the relatives of the drowned seamen and Mrs. Campbell.

The search for the bodies of the six victims of Sunday’s Carlingford

Lough disaster continued without result.

On Monday night the Lady Cavan passed over the spot where the

tragedy had occurred, captain and crew standing bareheaded as the steamer made

her way out of the Lough.

At a meeting of Carlingford Lough Commission on Tuesday 6 April 1937, the

Chairman (Lord Kilmorey) proposed that letters of sympathy should be

sent to all the relatives of the victims.

The motion was seconded by Mr. W. Moorehead, D.L. and passed in

silence, the members standing. The meeting was then adjourned as a mark of

respect. Afterwards the matter was discussed in committee, and arrangements

were made for a continuance of the search for the bodies.

At the first meeting of the newly formed Kilkeel Urban Council, the Chairman

(Mr. Edward McGonigle) read the following message from President de

Valera:-

‘I have learned with great sorrow of the deaths by the sinking of the Alder,

and I beg you to convey to the relatives of Captain and Mrs. Campbell

my sincere sympathy – Eamonn de Valera’.

On the motion of the Chairman, the members stood in silence in tribute

to their memory. The Clerk was instructed to convey the message to the bereaved

relatives.

At Newry Urban Council on Monday 5 November 1937 Mr. G.W.Holt, J.P.

referred to the recent shocking disaster in Carlingford Lough, when six people

– five from Newry and district and one from Belfast lost their lives and then

proposed a vote of sympathy with the bereaved relatives. The vote was passed

in silence

At a meeting of the Council of the Borough of Drogheda held on the 6 April

1937 on the motion of Alderman O. Kierans, seconded by His Worship

the Mayor (Alderman Walsh), a vote of condolence was unanimously passed

with the relatives of those who so tragically lost their lives on the ss

Alder in Carlingford Lough.

The Captain and crew were well known in the town and the tragic occurrence

came as a great shock to the citizens and the town clerk, J. Carr was

asked to convey to the relatives’ the deep and sincere sympathy of the Council

in their bereavement’.

At a meeting of the Carrickfergus Urban Council reference was made to

the tragic sea disaster which occurred in Carlingford Lough, resulting in the

loss of six lives and the clerk was directed to convey to the bereaved

relatives an expression of ‘the Council’s heartfelt sympathy and hope that all

will be comforted and strengthened in their sore trial.

BODY WASHED ASHORE

IDENTIFIED 7th APRIL 1937

On Wednesday morning 7 April 1937 the body of a woman, found washed ashore

at Rathcor, on

The body was found at a point six miles from Greenore, off which the vessel

sunk. It was clad in night attire, and a fur coat, and was identified by Mr.

William John Campbell, brother of Captain Campbell.

An intense search for the other bodies continued along the shores of the

Lough by police, coastguards and civilians. The remains were taken to the

licensed premises of Mr. Patrick Martin, Riverstown, Carlingford

and there an inquest was conducted on Thursday morning by Mr. J.H. Murphy,

solicitor, Coroner for Co. Louth. Evidence of identification was given by

Mr. Wm John Campbell, Kilkeel, a brother-in-law of Mrs. Campbell and the

inquest was then adjourned to a future date.

On Thursday 8 April 1937 the remains of Mrs. Campbell were conveyed

by boat from Carlingford to Greencastle, across the Lough and passed close

to the scene of the disaster. On arrival at Greencastle the remains were conveyed

by road to Kilkeel.

IMPOSING FUNERAL

IN KILKEEL OF MRS. CAMPBELL 9th APRIL 1937

Amid many manifestations of great grief the funeral of Mrs. Robert Campbell,

took place from the residence of her brother-in-law

Mr. Chas. Campbell,

It was a very imposing cortege, extending almost a quarter of a mile

long, and represented all creeds and classes from over a wide area. All

business in the town was suspended, windows shuttered and blinds drawn in

silent tribute to the deceased’s memory whose tragic death and that of her

husband and the other members of the crew of the Alder have occasioned grief

and sympathy. All shipping in

It was a touching sight to see the three little sons of the deceased, James,

Louis and Percy, march behind the coffin carrying

a wreath, which they placed on their mother’s grave after the internment.

The chief mourners included:-

Jim, Louis and Percy

Campbell (sons) and Isabella May Campbell

(daughter), Mr. James Campbell (father-in-law); Charles, Wm J. and

James and Harry Campbell; A. Kenmuir, G. Harper, R. Nicholson and R. Newell

(brothers-in-law); James and John Campbell, James Mitchell (uncles).

The remains were received in the Church by the Rev. H. Martin, M.A.

minister of Mourne Presbyterian Church, who conducted the funeral services

in the Church and at the graveside.

|

The assembly present sang ‘The Lord is my Shepherd’. Taking for his text: ‘Oh, death where is thy sting, oh grave where is thy

victory’. Rev. Mr. Martin preached a very touching and impressive

address. He said ‘ We in this church have all met on former occasion which have

been sad, but never on an occasion which is so full of sadness as the

present occasion’. ‘Robert Campbell, continued Rev. Martin, was a son of the

sea. He was born beside it and played along its shores as a boy. He

knew all its moods of storm and calm. Just before he embarked on what

was to prove his last voyage, he remarked that last winter was the worst

winter for storms he had ever experienced at sea. It is an irony of

fate that it was not in a storm but in a perfectly calm sea that the

brave Captain, his wife, and four other gallant men met their doom. Proceeding, Rev. Martin said that ‘he felt the present tragedy so

deeply that it was with difficulty he spoke of it. Captain Campbell,

he continued, was a powerful swimmer and could have saved himself but

he would not leave his wife to perish, and so in trying to save her,

the mother of his children, they were both drowned. ‘Greater love than this hath

no man, than he lay down his life for his friend’. In conclusion, Rev. Martin expressed his heartfelt sympathy with

the bereaved relatives, the sisters and the little children of Mrs.

Campbell, and the parents, brothers and other relatives of Captain

Campbell. |

|

| Minister of Mourne Presbyterian Church | ||

Included in the funeral cortege were the three young men who were rescued

off the Alder.

Messrs J. Fisher and Son were represented by Captain Connor,

Captain O’Neill and Superintendent James Torrens, while Mr. J. Birrels,

Manager, represented the

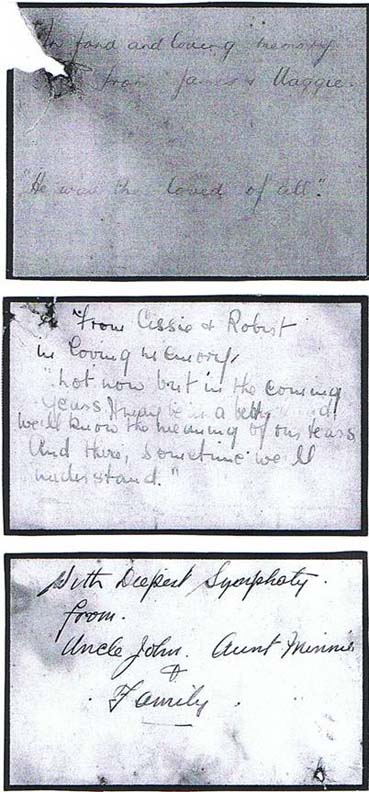

Amongst the many beautiful wreaths

were the following:-

‘In loving remembrance’, from father and mother.

From Robert’s sisters – Isabella, Cissie and Libby.

‘In affectionate remembrance’, from her sorrowing sisters and nephew at

Teacher’s Residence, Ballinran.

‘With deepest sympathy’, from Mr. and Mrs. R.E.Green.

‘To our darling mammie’, from her children.

From Uncle John, Aunt Minnie and Family

From Robert’s brothers; Wm. John, Charlie, James and

Harry.

Amongst the letters and telegrams of sympathy received was one from Right.

Hon. The Earl of Kilmorey, P.C.D.L.J.P. and one

from Mr. Eamonn de Valera, President of the

13th April 1937

A double breasted black overcoat of heavy material and comparatively new

in appearance found on the

The Carlingford Civic Guards daily patrol the extensive coast line in

their area.

INQUEST ON BODY WASHED ASHORE

AT

Mr. J.H. Murphy, Coroner for

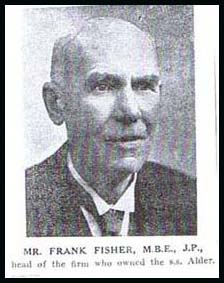

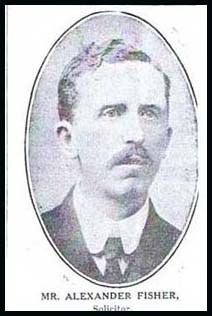

Mr. A. Fisher (Messrs. Fisher & Fisher, Newry) appeared for

the next-of-kin; Mr. Thos. M’Kinty (Messrs. M’Kinty& Wright, Belfast) appeared for the owners

of ss Alder; Mr. J.D.Chambers (instructed

by Mr. Robert Wallace, Belfast) for the owners of the Lady Cavan,

and Superintendent M’Donagh represented the Civic

Guards.

The Coroner said he had already taken a deposition from Wm. John Campbell,

who stated he was a brother of the deceased’s husband. He had seen the woman’s

body and had identified it. She was aged 39 and was married to Robert Campbell,

captain of ss Alder, the property of Messrs. Fisher, of Newry.

Deceased had gone with her husband on a trip from

Michael Sheelan, fisherman, Rathcor (Co.

Louth), deposed that he was at Rathcor shore at 7p.m. on 7th inst.

When he saw a bulk some distance away, and found out afterwards that it was

the body of a woman. He at once reported the matter to Guards M’Grath and

Darcy who went to the scene and removed the body to Riverstown. The body

was dressed in a singlet, short coat and a pair of stockings. There was a

slight mark on the nose.

Guard Darcy said it was dark when he reached the shore and he viewed

the body with the aid of a flash lamp. The remains were those of a woman dressed

in fur coat, vest, and stockings. There were some slight marks on the forehead

and nose. The body had been found at high water mark; the tide was practically

full in at the time witness was there.

Replying to the superintendent, witness said the shore was very rough

and rocky.

Dr. E.M. Finnegan, Carlingford, said the deceased was a well-nourished

woman of about 40 years. In witness’s opinion death was due to drowning. There

were several small bruises on the forehead, which he thought were caused by

the body coming in contact with stones on the seashore. There was a lot of

sand in the deceased’s hair and on her face. Deceased had no teeth – evidently

she wore dentures.

|

The Coroner said that was all the evidence he had in court, and if, Mr.

Fisher, representing the next-of-kin wished he might recall witnesses.

He (the Coroner) would have to have evidence that this lady was on the

boat. Mr. Fisher said there were two witnesses present. Mr. M’Kinty, representing the owners of

the ss Alder, said he was not calling any witnesses, but he willingly

left any available at Mr. Fisher’s disposal. Michael O’Neil, Victoria Locks, Newry, said he was mate on the ss

Alder, which belonged to the Newry and Kilkeel Steamship Company.

On April 3 they sailed from At 10.30p.m. on the 3rd they arrived

off the The Coroner asked for the address of the deceased, but Mr. Fisher

said Kilkeel was sufficient address, as Kilkeel was a small, though

important place. Superintendent M’Donagh said it was two

cables from the County Down side and seven cables from the nearest point

in The Coroner said, subject to what might be said by those representing the

parties, he proposed to find a verdict that deceased was found drowned

on the beach at Rathcor, on April 7, and death was due to asphyxia,

due to immersion in the sea in Carlingford Lough, on Greenore (County

Louth), on the 4th. Mr. Fisher asked that it should not be stated ‘Carlingford Lough

( Mr. M’Kinty – That is an international

question. The Coroner – I am not doing anyone any harm. Mr. Fisher – As no evidence had been produced to you whether it

was |

|

|

If you want your findings I will ask that the

inquiry be adjourned and we will bring experts. In justice to the relatives

of the deceased, it is not a fair thing to do. I ask you to say Carlingford

Lough, which is quite sufficient or Carlingford Lough, which lies between

Mr. Chambers said he did not want to put Mr. Fisher to any

trouble. He realised that Mr. Fisher was raising the matter for a technical

reason, but it did not affect the issue before the inquiry, which was to find

the cause of death. For his part he was agreeable to it being stated that

the body was found at a point in Co. Louth. He did not want Mr. Fisher

to feel that any difficulty was being put in his way as regards where deceased

died. He was quite agreeable that something neutral should be put in.

The superintendent – The only thing is that we claim the sea right round

the whole coast of

Mr. Fisher – It is inside, not outside.

Coroner amends verdict.

The Coroner amended his verdict to read that death was due to immersion

in the sea in Carlingford Lough, which lies midway between Co. Louth and Co.

Down.

Mr. Chambers, on behalf of the owners, master and crew of the Lady

Cavan, said he wished to tender to Mr. Fisher’s clients their deepest

sympathy. Those for whom he (Mr. Chambers) spoke were engaged in this

hazardous seafaring life, just as were those who had died, and on that account

their sympathy was very deep and sincere.

Mr. M’Kinty, on behalf of the owners of

the ss Alder, deeply deplored the tragedy and associated himself with

the expression of sympathy.

Superintendent M’Donagh said everyone

felt for the relatives, and especially for the unfortunate children who had

lost their parents.

The Coroner said it was one of the saddest cases that had occurred in

the district for many years. That they should have been so close to land and

yet met their deaths was a tragedy.

Mr. Fisher, replying on behalf of the relatives,

returned sincere thanks, and particularly to the Coroner for his action in

facilitating the identification of the body to permit burial without undue

delay.

It might be of interest to those present to know that at the funeral

service held in the Presbyterian Church at Kilkeel the Rev. Martin, who

officiated, bore public testimony to the kindness received from the Coroner,

the Guards, and all the people of the district.

The Coroner said he could assure the relatives that the officials there

were most sympathetic and tried to do their duty in the most humane manner

possible.

MEMORIAL

SERVICE TO THE LATE CAPTAIN

AND MRS. CAMPBELL

There was an extremely large congregation present on Sunday evening in

the Mourne Presbyterian Church, Kilkeel, when a memorial service for the late

Captain and Mrs. Campbell who perished in the recent Carlingford Lough

disaster.

The service was conducted by Rev. Herbert Martin, M.A. assisted

by Rev. Alfred Eadie, B.A.

THE ADDRESS

Basing his address on the text: ‘They that go down to

the sea in ships, and do business in great waters; these see the works of the

Lord, and His wonders in the deep’ (Psalm 107 v 23&24).

Rev. Martin said:

The session of this church invites the members of the congregation to make

this service tonight a memorial in the highest sense, and to join in this

expression of public sympathy with the

As the minister of the

What secrets it holds in its wild and wandering waters- secrets that will

not be revealed till the sea gives up its dead :

Thou goest forth dread, fathomless, alone’. Mrs.

Henmans, in her poem, ‘The Graves of a Household’, with

a plaintive melody touches the ground tone of many a mother’s heart: -

‘The same fond mother bent at night

O’er each fair sleeping brow;

She had each folded flower in sight,

Where are those dreamers now?

The sea, the blue lone sea hides one,

He lies where pearls lie deep;

He was loved of all, yet none

O’er his low bed may weep.’

Isaiah said’ There is sorrow in the sea – It cannot be quit.’ There is a

wistful fascination about the sea, it draws and holds. What is its influence?

That is part of its mystery.

In a little book called the ‘Surgeon’s Dog,’ one of the seamen says to

the young surgeon taking his first trip: ‘Don’t stay with us long if you don’t

mean to stay with us always, for once the sea gets you it will never let you

go.’

Robert Campbell was born by the sea; the first sounds he heard were

of the sea. Its vast expanse was amongst the first things he saw. As a boy

he played by the dancing waters. He grew up intimately acquainted with its

storm and calm. He knew the restless moods, the whimsicalities, the

diapason of the sea. His spirit was attuned to the music of the waves. Such

a man possessed the essential qualities of a great seaman – keen, intelligent

and without fear he answered the call of the sea. His home was on the sea.

One of his shipmates said of him ‘He would take you into storm, but he could bring you out of

it again.’ He always did. Just before he set out on his last voyage he declared

the past winter to be the worst in weather he had experienced in all his twenty years at sea. It has

been a winter of storms, and every storm has been a gale.

Isn’t it a strange irony of fate that such a man should lose his life

when the sea was calm as the face of a sleeping child.

But he knew that a fog at sea is more to be dreaded than a storm, for

there the seaman does not fear the sea, but those who sail on it. There the

careful man is at the mercy of the careless and, indeed, the good seaman is the

enemy of the best.

Only a clever man could bring his vessel across the bar in the fog that

lay over Carlingford Lough that night. He knew the Lough – he knew how far to

go and when to stop. And only a skilled and careful hand could drop anchor

where he did – well out of the fairway, so as not to endanger other shipping.

I have been over the ground and within a few yards of the Alder’s

masts and funnel. They are a melancholy sight, rising upright from the water,

dignified in death. Experts will give their views on the position of the wreck

and it is not for me to say if the disaster could have been avoided or averted.

But the blow has fallen – Captain Campbell and his wife are gone, and

with them four brave seamen. It is said to be the worst disaster since the

sinking of the ill-fated

But black as this disaster is, it is shot through with rays of fine nobility.

Captain Campbell could easily have saved himself. He was a strong swimmer.

He was last seen standing with his wife on deck, awaiting an opportunity to

bring her to safety, while the others rushed to man the lifeboat, little dreaming

that the Alder was so badly damaged, and was sinking like a stone.

And in the vain effort to save his wife he lost his own life as well. ‘Greater

love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his

life for his friend.’ The large concourse of men at Mrs. Campbell funeral

was a genuine tribute of public sympathy. And here in this memorial service

I wish to recall the kindness received by Captain Campbell’s brother

from the people on the other side of the Border when he went to bring home

the remains of Mr. Campbell. The kind people there, and especially

the Sergeant of the Civic Guards, did everything they could to make this melancholy

offices as light as possible. Before such a human tragedy, thank God, all

our divisions disappear

– borders and boundaries melt into one: ‘One touch of nature

makes the whole world kin.’ A disaster like this makes deeper impressions

than we know.

Our characters must in some way

assimilate our pain. Three of our membership this year lost their lives at sea.

The wounds will heal but the scars remain, and those who sit in solitude

and mourn will see the scars the plainest. We, in the deepest sympathy for

them, will tell them that we will remember too.

Captain Campbell’s wife and children were

his darlings. Much as he loved them he never lost touch with his own parents

and his home family.

That fact has made natural for the children to turn to them and to find

with them all that a home should be to children who have lost their earliest

and truest friends. ‘The true way to mourn the dead is to take care of the

living who belong to them’.

There is a line in an old Greek play which says:’ The youthful mind is

not won’t to grieve,’ and yet these children are old enough to go into the

years with a memory that love will not let die till ‘ the

day break and the shadow flee away.’

‘You may shatter the glass in which roses distil,

But the scent of the roses will hang round it still.’

Life is like a troubled sea – we are voyagers – but we need not be helpless

victims of uncertainty, for we have with us One Who knows the sea, One Who

walked to meet the disciples on the

The praise portion of the service was led by the choir under the capable

direction of Mr. W. J. Chambers. Both choir and congregation gave a

sympathetic rendering of the 42nd Paraphrase: ‘Let not your hearts

with anxious thoughts be troubled or dismayed.’

The service concluded with the singing of the hymn: ‘For ever with the

Lord.

LOSS

OF THE ALDER- CLAIM and COUNTER-CLAIM in

Thursday 6th May 1937&

Friday 7th May 1937

Continuation of Evidence

Following further evidence on behalf of the Newry and Kilkeel Steamship

Co., Ltd., the master and crew of the Lady Cavan gave their account

of the accident in Carlingford Lough in the early morning of April 4 in the

Admiralty Court, London, on Thursday, when Sir Boyd Merriman, sitting

with Elder Brethren, continued the hearing of the action and counter-claim

arising out of the collision.

The action was brought by the Newry and Kilkeel Steamship Co., Ltd.,

owners of the Alder, who claimed damages from the British and Irish Steampacket

Co. (1936) Ltd., owners of the Lady Cavan.

The Lady Cavan, in counter-claiming, said she was misled by the Alder’s

anchor lights.

Having seen what she supposed to be the side lights of a vessel at

anchor, the Lady Cavan saw a further light, which she took to be that of

the No. 12 buoy, and she aimed to pass between it and the vessel. It was in

fact the Alder’s stern light.

It was further suggested by the Lady Cavan that the Alder

was not ringing her bell in accordance with the fog regulations and did not

sound her whistle, and that she was lying athwart the fairway.

The Alder pleaded that, bound from

PARAFFIN LAMPS

The mate of the Alder, Michael O’Neill, in answer to the

Judge, said the anchor lights were not the only lights to be seen from his

vessel. Lights were in all the cabins.

Some portholes might have curtains, but all of them had not. Some of the

lamps were hanging; some were in brackets.

The mate agreed with Mr. Noad, K.C., for

the Lady Cavan, that while there was a light in the captain’s room

and a lit swinging lamp in the mess-room, the mess-room curtains were usually

drawn for it was not desirable to have a glare upon decks at night time. The

lamps were paraffin and he did not think a vessel approaching him broadside

on could see the chimney and lighted burner of any lamp.

MASTER OF THE LADY CAVAN

Captain John Gallimore, of the Lady Cavan, gave evidence

of how he approached the Alder. He saw two lights, the lower a shade

to the left of the higher. He presumed they were on a vessel lying to the

flood end on with her head towards him. He intended to pass down her port

side to come to an anchor and was heading clear. The he saw a further light

lower than the others. He ordered the helmsman ’Hard aport (to lift her head

quicker), go between the ship and the buoy.’ Then he saw the hull of the vessel.

After collision he kept the Alder alongside with a rope for five minutes

till she began to heel. He called the crew to come on board and threw out

lifebelts. His speed had been about two knots. He thought the crew of the

Alder was preoccupied with getting their own lifeboat because the captain’s

wife was on board. They could quite well have stepped from the deck to the

Lady Cavan, though the necessity was not at first apparent.

From first seeing the lights of the Alder to the collision was

about a minute. He did not sound his whistle when the fog came on, though he

slowed his engines as a precaution.

The Judge – Why did you not sound your whistle?

The Captain said the weather did not appear thick enough.

They were coming up from

He had rung ‘slow’ at 4.10, he gathered from consulting the engineer’s

record just after the collision, and his speed would be four knots at sighting

and two knots when he struck.

Answering the Judge, Captain Gallimore said that travelling full

speed it would take about six minutes to pass from No. 10 Buoy to No. 12 Buoy.

The distance was just over a nautical mile.

On the distance from No. 10 Buoy the light could not have been No. 12

Buoy, but was misled by supposing the visibility was better than it was

Sir Boyd Merriman made the comment that the captain jumped to the

conclusion that the light was on the buoy although he saw the light on his

port bow, and the buoy must have been half a mile away.

DID NOT WANT CHAIN ROUND

PROPELLER

Witness replied that when he ordered hard aport wheel and full ahead he

did not want the chain round his propeller.

His Lordship added if witness thought he was near No. 12 buoy he must

have travelled faster than he admitted.

Captain Gallimore said his look-out man had only been in the ship

six days. The man, he thought, did not report lights and signals coming up.

He asked the mate about him after he rang ‘Slow ahead’

The Judge – The Elder Brethren who are assisting me would like to know

whether it is the practice in this ship, in reporting lights ahead, to include

the lights of buoys.

Captain Gallimore said it was.

His Lordship remarked that the vessel must have passed one light after

another without a hail.

The Captain said he called for the chief’s record immediately after

The chief officer of the Lady Cavan, Mr. John Joseph Higgins

said he took the last light to be the No. 12 Buoy on the port bow, though

normally the No. 12 Buoy would appear on their starboard hand.

Frank Giles, of the Lady Cavan said the engines had been

going astern for 15 seconds when the collision occurred.

A young man Hugh Hollywood, look-out on the forecastle head said

he reported the first two lights but the collision came before he saw the

Alder’s stern light.

The hearing was then adjourned till Friday.

THIRD DAY

The Judge had noticed the indication of an erasure in the Engineer’s Log

among the records of the engine movements round about the of collision, and

Mr. Robert Wright, the superintendent engineer of the British and Irish

Steampacket Co., went into the box and explained that when he was going through

the records at Newry with the engineer he lightly placed a mark at a passage,

as he frequently did he going through his papers.

Having made the pencil mark, he at once said ‘I should not have done

that. We must rub it out’ and he directed the engineer to take out the pencil

mark. He had been asking about the point when the engineer felt the contact

with the other ship.

Mr. Carpmael, K.C. (for the Newry

and Kilkeel Steamship Co.) asked was the mark place to indicate the moment

of contact?

Mr. Wright replied not the actual moment of contact. The mark led

down from immediately before the contact to the point of contact.

The Judge directed Mr. Wright to come on the bench and look at the

log through his magnifying glass;’ I never thought much about the erasure’

added the judge. ‘I am more interested in the next page.’

Mr. Wright turned over the page which bore the erasure mark and

observed that the page bound next after it in the book had obviously disappeared.

The Judge went on – ‘Do you see upon what becomes the next page, not

pencilled figures, but the impress of pencilled figures and the letters ‘a.m.’

Where do you think those pencilled letters were made?’

Mr. Wright said he could only suppose they were made on the page

which was missing. He thought possibly a blank page had been taken from the

end of the book and that had liberated the page about which his Lordship was

curious.

DECISION

The Court found that the Lady

Cavan was 4-fifths liable and the Alder one-fifth liable for the

collision, and apportioned the costs of the proceedings accordingly.

The damages will be assessed

on this basis later.

A record of clarity in the

Messrs. McKinty & Wright,

CLAIMS BY NEXT-OF-KIN OF

VICTIMS

Messrs. Fisher & Fisher, solicitors, acting on behalf of all the victims of the collision, having

issued writs for damages against the British and Irish Steampacket Co., Ltd.

(owners of the Dundalk & Newry Steampacket Co., Ltd.), and same will come

on for hearing in the Northern Ireland High Court of Justice at Belfast.

The victims were:-

Captain Robert Campbell, Kilkeel, who left four children

Mrs. Catherine Campbell, his wife.

Chief Engineer Robert McGrath,

Second Engineer James Davis,

Jack Gorman, Rooney’s Terrace, Newry, deck hand (unmarried)

John Conlon,

CARLINGFORD LOUGH

DISASTER; ANOTHER BODY FOUND 9th May 1937

VERDICT OF ‘FOUND DROWNED’ RETURNED

at inquest on 10th May 1937

The shipping disaster in Carlingford Lough on 4th April last

had a further sequel on Sunday 9th May 1937 when the body of a

second victim – John Gorman, Rooney’s Terrace, Newry was recovered.

The body of Mrs. Catherine (Kate) Campbell who was drowned with

her husband Captain Robert Campbell, and four members of the crew of

the ss. Alder, the sunken Newry vessel was

recovered on 7th April, although an inquest did not take place

until 16th April 1937.

It will be recalled that the Alder, a vessel owned by Messrs.

J. Fisher & Sons the Newry Shipping Firm sank in Carlingford Lough

following a collision with the Lady Cavan.

Of the nine persons aboard the Alder, only three were saved.

Gorman’s body was seen floating in the Lough between Greenore and

Carlingford by members of a steamer making for Newry and the matter was reported

to the civic guards on the Louth shore of the Lough, and the R.U.C. on the

County Down side. The shore was immediately patrolled on both sides and at

4.20pm. when the tide had ebbed, the body was recovered

by Guard James Reynolds.

Two of Captain Campbell’s brothers made the journey across the Lough to

Carlingford when relatives of others who had lost their lives also attended on

Sunday evening.

The body was identified as that of Gorman, and an

inquest was conducted in Carlingford Courthouse on Monday morning by Mr. J.M.Murphy,

coroner, and Superintendent McDonagh represented

the police.

The first witness was Miss Mary Gorman,

Michael O’Neill, Victoria Locks, Newry, mate of the Alder, and

one of the survivors, said that he saw Gorman on the deck immediately

after the collision and did not see him alive afterwards. He identified the

body as that of John Gorman.

Guard J. Reynold said he was on patrol duty and saw the body floating

on the Lough about 500 yards from the shore at 2.30pm. He waited until the ebb,

about 4.20pm. and recovered the body from the shore in

the liberties of Carlingford.

Dr. Finnegan, who examined the body, said it was that of a man of

about fifty years of age and 5 feet 7 inches in height. Deceased had on black

boots, grey socks, brown dungarees, leather belt with buckle, greyish-black

shirt with short tucked-up sleeves. The hair was grey. The knees and chest

were injured – the skin being off – leading him to believe that the body was

that of a man who had been drowned about five weeks

previously.

The Coroner found that the deceased, John Gorman, was found drowned,

the cause of death being drowning due to immersion in the sea in Carlingford

Lough which lies between Counties Louth and Down.

He said he would record in his findings an expression of sympathy from himself

and he wished to repeat what he had said on the occasion of the previous inquest

at

The Superintendent of Guards joined in the expression of sympathy.

Mr. Alexander Fisher (Messrs. Fisher and Fisher, solicitors, Newry)

said Mr. Wallace,

solicitor for the owners of the Lady Cavan had asked him to state that

the owners of the Lady Cavan desired to repeat the expression

of sympathy already extended. Mr. Fisher said the owners of the Alder,

through him, desired to express the greatest sympathy with the deceased’s

and all other relatives. He said he represented the relatives of the deceased

and on their behalf desired to return most sincere thanks for all the kindnesses

which had been shown the relatives at the time of the discovery of the body

on Sunday afternoon and during the terrible ordeal of identification; also

at the inquest that day. He also said they wished to bear testimony to the

most commendable elasticity exercised in the Border regulations when vehicles

were passing and repassing to Carlingford; and also

to the arrangements made for and facilities given to the relatives in having

the body taken across the border.

Mr. Fisher also thanked Captain McKevitt,

harbour master at Greenore, for his assistance.

The funeral took place at St. Mary’s Cemetery, Newry, yesterday

amid many manifestations of regret

The chief mourners were – Misses Bridget and Mary Gorman (sisters),

Messrs. Harry Gorman, John Gorman and Jim Gorman (nephews), Mrs.

Gorman (sister-in-law), Misses Dora and May Gorman, Mrs. Brady, Mrs.

Campbell, Mrs. Trimble (nieces), M. K. Hughes, Mrs. Hagans,

Mrs. Hearty, Glasgow; Mrs. Malone, Mrs. Murphy, John Hughes, Hugh and

Paddy Golding (friends)

Wreaths were received from Mrs. McGrath,

Rev. Father Campbell, in the course of a touching panegyric, said

the Holy Spirit warned them to be prepared because they knew not the day or

the hour when the Son of Man cometh. They saw life all around them and death

occurring sometimes in unusual and peculiar circumstances. Death always brought

sorrow and sadness, but when it came in tragic and sudden circumstances the

blow was more severely felt. On that occasion they were paying their respects

to one who had been called away in sad and tragic circumstances, and it was

sufficient for them to remember that Christian charity required their prayers

on behalf of the soul of him who so suddenly lost his life. They knew that

death took him unexpectedly and suddenly, and he may not fully have realised

that death was about to take place. Even though death has come suddenly they

felt he was not entirely unprepared.

He had been a man with a kind and charitable heart, and had been

faithful to his Christian duties. They had every confidence that God in his

mercy would take him to a happier existence than in his earth. He expressed

heartfelt sympathy with the sorrowing sisters and other relatives

BODY FOUND AT WHITEHAVEN

THAT OF ANOTHER LOUGH VICTIM?

Messrs. Fisher & Fisher , solicitors , Newry, are in touch with

Whitehaven police on behalf of Mrs. McGrath, Erskine Street, Newry,

as to the possibility of a body found at Whitehaven being that of her husband

Robert McGrath, chief engineer of ss. Alder who was drowned

when the ship sank on April 4th last.

The police authorities have given information to the effect that the

body was buried on Friday last (7th May 1937), but that they had

retained the clothing for identification purposes.

The clothing and other articles found on the body are to be dispatched

to the Bridewell police, Newry, so that Mrs.

McGrath may have an opportunity of inspecting them.

SUNKEN

COLLIER RAISED; ECHO OF CARLINGFORD COLLISION

The salvage work to retrieve the Newry collier Pine, which was

sunk in Carlingford Lough last November and which has been in progress at

intermittent periods during the past couple of months, was brought to a

successful conclusion on Saturday (8th May 1937), when the vessel

was removed from the fairway and brought close in to deep water at Greenore.

There is now no danger to navigation in the fairway, and the buoy marking the

wreck has also been removed.

The working of lifting the Pine was carried out by Mr. Samuel

Gray, salvage contractor,

Captain Campbell who lost his life, as

also did his wife and three of the crew when the Alder was sunk at

the beginning of April, was in charge of the Olive when she collided

with a sister ship (the Pine) which then sank in the Lough. No lives

were lost on that occasion.

CARLINGFORD

LOUGH DISASTER- A

THIRD BODY WASHED ASHORE DISCOVERY AT ANNALONG

Another body, identified as that of James Davis, aged 46 years,

The body is the third to be recovered, the others being that of Mrs. Campbell,

Kilkeel, wife of the Captain of the Alder, who was also drowned, and

that of John Gorman, deck hand.

It appears that about eight o’clock on Sunday evening, Mr. Bob McKibben and Mr.

Sidney Chambers, Annalong, saw

a body floating on the incoming tide at Annalong. They informed the police

and Constable Patterson accompanied

by Mr. T. McBurney, tailor,

went to the scene and recovered the body from the sea.

The body was in an advanced state of decomposition, and was removed to

Mr. Robert Gordon’s licensed

premises at the Harbour, Annalong.

The body was clad in a blue double-breasted coat and dungarees, and in

the pockets were found a union key, attached to a chain, and a cigarette

lighter.

The Coroner for South Down, Mr. R. S. Heron, was communicated with, and also the relatives of the three

men who are still missing from the wreck of the Alder eight weeks ago.

Mr. Alex Fisher, accompanied by Mr. Conlon, Newry, son of

Mr. J. Conlon, who perished in the disaster,

and Mrs. McGrath, Newry, wife of Mr. R. McGrath,

who was also drowned at the time, arrived at Annalong on Sunday night and

inspected the remains, but recognised that the body was not that of either

of the two missing Newry men.

The remains were identified by Mr. S. F. Kelly,

Mr. R. S. Heron, coroner for South Down, conducted the inquest yesterday,

when District Inspector Silcock represented

the police and Mr. Alexander Fisher appeared on behalf of the relatives.

Samuel F. Kelly, brother-in-law

, said the deceased was 46 years of age and was second engineer on

board the Alder at the time of the disaster. He had identified the

body.

Michael O’Neill, Victoria Locks, Fathom, Newry, one of the survivors

said he had been mate of the Alder at the time of the disaster. He

had known the deceased and remembered 4th April last when the vessel

was returning form Irvine to Newry, and had anchored in Carlingford Lough

on account of the fog. Between 4 and 5 am. On 4th

April the Lady Cavan struck the Alder amidships and the vessel

sank n a few minutes afterwards. Deceased perished with the others.

Robert McKibben,

The jury, of which Mr. Isaac Hamilton was foreman, found that death

was due to drowning in Carlingford Lough on 4th April and added

a rider expressing sympathy with the widow and children and other relatives

of deceased.

District- Inspector Silcock also joined

in the expression of sympathy on behalf of the police.

The Coroner said that in common with so many people and various public

bodies he extended his sympathy to the relatives. The sinking of the Alder

was undoubtedly a very sad affair but not so

terribly sad as on the occasion of the sinking of the ‘

Mr. Fisher, returning thanks on behalf of the relatives, paid tribute

to the people and the police of Annalong for the assistance they had rendered

in the recovery of the body.

The remains were removed to

THE

LOSS OF THE ALDER; CHIEF

ENGINEER’S BODY FOUND 26TH May 1937

On Thursday evening, Mr. J. H. Murphy (Coroner for North Louth)

held an inquest in the licensed premises of Mr. John Finnegan, licensed

publican, Whitestown, regarding the finding of the body of Mr. Robert

McGrath, chief engineer on the Newry collier Alder, who was drowned

in Carlingford Lough, when the collier when at anchor was sunk in collision

with the Lady Cavan on the 4th April 1937.

Inspector O’Mahony, Civic Guards, conducted

the proceedings, and Mr. Alex Fisher appeared for the widow of deceased.

Mrs. Madeline McGrath.

Michael O’Neill, mate on the Alder on the morning she sunk,

said the deceased was aboard on the morning of the collision. Witness last

saw him on deck as the vessel began to sink. He identified the remains by

the one-piece boiler suit which deceased wore, also by the gold watch and

coronation knife.

Guard Francis McGrath, Carlingford, gave evidence of finding the

gold watch, coronation knife, etc, on the body.

James Finnegan, Whitestown, stated that

about 4 o’clock on the evening of the 26th he sighted a body about

a mile off Ballagan shore, and with a pair of marine

glasses he satisfied himself that it was a human body. The wind at that time

was due south and the body was drifting in towards the rocks. The wind, however

changed, and witness and James Killen got a boat and brought the body

ashore about 10 o’clock that night, afterwards reporting the matter to the

Civic Guards at Carlingford.

Dr. Finnegan stated that death was due to drowning.

The Coroner recorded a verdict of death form drowning in Carlingford

Lough, and expressed his sympathy with the widow and family of the deceased.

Mr. Fisher, on behalf of Mrs. McGrath and family suitably

acknowledged the vote of sympathy, and said he desired to thank the Civic

Guards, and the people of Whitestown, and especially

James Finnegan and James Killen for what they did in recovering the body

Mr. Robert

McGrath's Funeral , Friday 28th May 1937

Amid many manifestations of regret the funeral of Mr. Robert McGrath

took place on Friday to Mullaghglass New Burying

Ground.

A service was conducted in the house by Rev. R. A. Swanzy,

B.A., Vicar of Newry, and Rev. Dr. Martin, Mullaghglass,

officiated in

The chief mourners were: Mr.

James McGrath, Belfast (brother); Master Allan McGrath (son); Messrs.

Harold Thompson and Stanley Briggs and Robert Briggs (brothers-in-law);

Mr. James McGrath, Barrack Street, Newry (cousin); Messrs. James

Thompson, David Hawthorne, Herbert Nelson, George Heasley,

James Bradley, Gerald Bradley (Bessbrook), W. Holmes sen.,

William and John Holmes, David McElroy (relatives)

The three survivors of the disaster were present, viz., Michael O’Neill,

Newry, Jim Hollywood, Newry and W. Cahoun, Carrickfergus.

Messrs. Joseph Fisher sons, owners of the ill-fated ss. Alder were represented at the funeral.

Wreaths were inscribed as follows:-

‘From his sorrowing wife and family’

‘In remembrance of Bob’ from his sister Mrs. Thompson

and his nephew Harold.

‘With deepest sympathy’ from Misses Gorman

‘With deepest sympathy’ from Mr. and Mrs. Caldwell

and family,

‘With deepest sympathy’ from Mr. and Mrs. McElroy, Basin Walk, Newry

‘In fond remembrance’ from the Briggs family, Craigmore.

Numerous messages of sympathy were received.

The late Mr. McGrath is survived by his wife, one son, Allan,

and two daughters, Misses Beatrice and Muriel McGrath.

Mr. W. Heslip,

Newry Reporter Saturday

19th June 1937

It is probable that the claims for damages on behalf of the dependents

of the victims of the disaster will come before the

Mr. E.S. Murphy, K.C. M.P.; Mr. A. Black, K.C., M.P.; and

Mr. W. Johnston (instructed by Messrs. Fisher & Fisher)

represented the plaintiffs, and Mr. J.C. MacDermot,

K.C., and Mr. Chambers (instructed by Mr. Robert Wallace) were

for the defendants.

THE

ALDER – LADY CAVAN COLLISION MOTION IN COURT OF APPEAL ; DAMAGES

ACTION TO START ON MONDAY 28TH JUN

The collision in Carlingford Lough on 4th April between the

Newry collier Alder and the passenger-cargo steamer, Lady Cavan,

as a result of which six persons lost their lives, had a further sequel in

the Belfast Court of Appeal on Friday 20th when Lord Justice Best and Mr.

Justice Megaw heard an appeal by the defendants in the pending claims

for damages against the order made by Lord Justice Andrews, refusing to stay

the trial of the actions.

The claims for damages on behalf of the defendants will come before the

The plaintiffs in the actions are: - Robert James Campbell and others,

dependants of the captain of the Alder and his wife; Madeline McGrath,

Rose Conlon, and Margaret Davis, dependants of other members

of the crew of the Alder; and the defendants are the owners of the

Lady Cavan, the British and Irish Steampacket Co. (1936), Ltd.

FOUR ACTIONS

Mr. J. D. Chambers said his clients were appealing from an order

made by Lord Justice Andrews refusing to postpone the trial of those

actions which were originally fixed for Monday next. There were four actions,

ordered to be tried together, arising out of the unhappy deaths of a passenger

and members of the crew of the steam ship Alder, who lost their lives

by drowning as a result of a collision between that vessel and defendant’s

vessel, the Lady Cavan. The actions were brought by persons who were

dependants of the victims and the pleadings were the same. In the case of

Campbell, who was master of the Alder – and although he and

his wife lost their lives – there is a plea of contributory negligence against

his representative alleging that there was contributory negligence on his

part leading to the disaster.

Mr. Chambers continuing said, Proceedings to fix the responsibility

for that collision were instituted in the Admiralty Division of the High Court

in London, and those proceedings came before the President of the Division

on the 5th, 6th, and 7th May this year. By

his findings, the President assigned the blame as four-fifths upon the Lady

Cavan, owned by the defendants and one-fifth on the Alder.

THE LOG BOOK

During the course of the trial the engineer’s scrap book which purported

to show very material records of speeds of the Lady Cavan was produced

and criticised by the President. As the President said in his judgment he

thought it right to institute an inquiry as to whether or not the entries made

in that log book were true. That was to say whether they were made at the time;

whether or not there had been removal of pages from that book

That book was discredited at the

Lord Justice Best – There has been no delay about this

Mr. Chambers – Certainly not.

EXPERT’S AFFIDAVIT

Mr. Chambers read an affidavit by Lt. Col. Mansfield, expert,

in which he said the book was collected on 15th June. It would

take him ten days to examine the book.

It was essential that the hand writing expert’s examination of that log

book should be carried out so that the very serious reflections on those who

testified as to that book should be removed, if possible. Recognising that that

book goes to the root of the actions – it showed the speeds at which the boat

was travelling – the experts report was crucial to the case.

Proceeding, Mr. Chambers said the expert apparently intended having

ultra violet photograms taken of the log book, and

also subjecting it to other scientific processes. The main allegation against

his client was with regard to the speed and the allegation against the Alder

was that she was carrying misleading lights.

CRUCIAL EVIDENCE

Mr. Chambers said if the expert found that if the book did not present

the appearance of having been tampered with, surely it would be a matter of

very great importance if in support of the claim, an attack was made upon

the log book. His evidence was crucial. He submitted that they must be given

an opportunity to present the evidence if it could be presented.

He (Mr. Chambers) was in this position – that if the expert found

the book did seem to show that the suspicions of the President were well founded

no attempt would be made to call another expert.

CORRECT CONCLUSION

Opposing the granting of the stay, Mr. Murphy said that Lord Justice

Andrews had arrived at a most correct conclusion on the facts of the

case. It must be conceded that to the defendants it was a matter of the very

greatest importance that at the earliest moment they should be in a position

to assert their rights.

Mr. Justice Megaw remarked that the Admiralty action was tried in

a very short time.

Mr. Murphy, continuing said there was in fact some delay between

the delivery of the statement of claim on the 7th May and the delivery

of the defence. It was on affidavit and the letters were accepted on 13th

May, six days after the judgment was delivered in the Admiralty action, wrote

Messrs. Fisher & Fisher requesting an extension of time for a week

or ten days in order to allow him to have the defence delivered. Six days

after the judgment Mr. Wallace, presumably on the instruction of his

Continuing Mr. Murphy said, that during

the three day hearing in the

PREPOSTEROUS SUGGESTION

It was perfectly preposterous, continued Mr. Murphy, to suggest

that it would take an expert a month to decide whether a page had been torn

out of a log book.

Mr. Murphy added that he should be delighted to cross-examine that

expert on the ultra violet photograms or on his

time and examination.

Mr. Chambers said there was grave danger of an injustice, and the

log book was on of the most vital pieces of evidence, and an essential piece

of evidence for his clients. Until that document and its authenticity had

been inspected, he submitted there should be no trial.

Lord Justice Best said they had two issues to decide. First – would

it materially interfere with the interests of justice so far as the defence

was concerned? And in the second place, should they interfere with the discretion

of the learned judge, who fixed the hearing of the trials for Monday.

Neither he nor Mr. Justice Megaw was satisfied that it would be

an injustice to one or other of the parties, if the trial were to go on. They

refused the application, which they dismissed with costs.

Mr. Justice Megaw concurring complimented Mr. Chambers on

the splendidly clear manner in which he had presented his case

| Remains of the Alder |  |

THE ALDER – LADY CAVAN

COLLISION; DEPENDENTS OF VICTIMS CLAIM COMPENSATION

HEARING OF FOUR ACTIONS -28th JUNE 1937

The hearing was commenced, on the

28 June 1937, before Lord Justice Andrews, in the King’s Bench Division of the Ulster High Court

yesterday of the action for compensation for the loss

of five lives as a result of the collision in Carlingford Lough, on 4th

April last, between the Newry collier Alder and the Lady Cavan,

a passenger-cargo vessel, trading between Liverpool, Newry and Dundalk.

The plaintiffs were Robert James Campbell and others, dependents

of the captain of the Alder and his wife; Madeline McGrath, Rose

Conlon, and Margaret Davis, dependents of three other members of the crew

of the Alder, and the defendants were the owners of the Lady Cavan,

the British and Irish Steampacket Co. (1936) Ltd.

Mr. E. S. Murphy, K.C.; Mr.

A. Black, K.C., M.P.;

and Mr. W. Johnston (instructed by Messrs. Fisher & Fisher)

represented the plaintiffs,

and Mr. J. C. MacDermott, K.C.,

and Mr. Chambers (instructed by Mr. Robert Wallace) were for

the defendants.

Mr. Johnston, opening the case, said defendants denied that they

were guilty of any negligence and in the case of Robert Campbell, deceased,

they said he was guilty of contributory negligence.

PLAINTIFF’S COUNCIL

Mr. Murphy said there were four actions and it had been agreed as

all the actions arose out of the same catastrophe that they should be tried

together. In the first action the claim was made on behalf of Robert Campbell.

He was a young man, aged 42, and most unfortunately on this occasion when

his ship ss. Alder was sunk his wife was on board and she was drowned

with him. Claims arose in connection with the loss sustained by the children

of both father and mother. There were four children – Robert James, aged

16; Isabella May, aged 14; Henry, aged 12 and Charles Pearson, aged 9.

Captain Campbell had a weekly

wage of £5 10s when at sea.

The second action was brought by the widow of William

Robert McGrath, chief engineer, who lived at Newry. He was

47 years of age. They had three children, Beatrice, aged 19; Muriel, aged

11; and Alex, aged 7.

The chief engineer’s wages when he was at sea were £4

9s 3d per week, and in the previous two years his earnings

were £166 and £232 respectively.

The third action was brought by Rose Conlon in respect of her husband

John Conlon, who

was a fireman, aged 52. They had two children, John, the

elder and Jane aged 19. The father earned

£3 2s per week and in the previous two years his totals were

£92 and £144 respectively.

The fourth action was brought by Margaret Davis, widow of

James Davis, second engineer, who was 48 years of age. He lived on the

Mr. Murphy proceeded to review the facts which were to be given

in evidence.

NEWRY ARCHITECT

The first witness called for the plaintiffs was Mr. S. Wilson Reside,

C. E., Newry, who stated he had actual experience at sea being an engineer

on the Headline for a time. On the 12 April this year witness made

an inspection of the ss. Alder in the position in which she now lies

in Carlingford Lough. On that date he took a number of bearings. On the 1st

May he made another inspection and took the position again. On the same day

he took the position of the buoys in the Lough and prepared a map which was

now before the jury. On the 15th June he made a further inspection,

accompanied by Mr. James Torrens, of Messrs. Fisher & Sons,

and Mr. Wm. John Press. He sailed over the course taken by the vessel.

The Carlingford Channel was a buoy channel maintained by the Carlingford Lough

Commission. The buoys bore numbers, which were painted on them. There was

a lighthouse at No. 6 buoy, called the Hawlbowline Lighthouse.

Continuing witness said that a fathom was 6 feet and a cable 600 feet.

There were 10 cables in a nautical mile, and 6008 feet in a knot. The situation

of the Alder where she is now lying was two and two thirds cables, or

1,600 feet from Greenisland. At the present time her bow was pointed towards Greenisland.

As regards the channel, she was laying two thirds of a cable clear of the

channel.

LYING IN CHANNEL

Lord Justice Andrews – Is she lying in the channel? – Yes, she is

150 feet from the North side of the channel.

Lord Justice Andrews – She was not off her course in any way? –

No.

Mr. Reside said that the distance from the Hawlbowline Lighthouse

to where the Alder now lay was about 8,800 feet. Assuming that a vessel

covered that distance in ten minutes her average speed would be 8 and two

thirds knots per hour. From No. 10 buoy to the Alder would be about

4,500 feet. If it covered that distance in 6 minutes, the sped would be about

7½ knots.

Cross-examined by Mr. MacDermott – May I take it as right that one

knot per hour is 100 feet per minute? – Yes, 100 feet.

How far is it from the Bell Buoy to where you marked the wreck of the

Alder? – Almost 10 cables.

What would the average speed in knots be? - 4¾ knots

per hour.

Can you tell me the distance between the Bell Buoy and the Upper Pine Light? – About 27

cables.

Are you familiar with the routes about the Bell Buoy? – Not outside it.

Do you know from your knowledge that vessels coming from

The Alder, when sunk, is lying clear of the channel, - She is

lying a little bit inside.

I take it she is not clear of the channel? – A little bit in the

channel.

Assuming that she was sunk where she was struck, was she on her course?

Do you agree with that? – I do.

James Torrens, superintendent engineer of Messrs. Joseph Fisher

& Sons, ship owners, Newry, stated that he had experience as an engineer

on a ship, and that he held a chief engineer’s certificate since 1904. He

produced a document which gave particulars of the Alder. On 26th

April he inspected the lamps of the Alder. There were two hatches –

one forward and one aft. When witness examines the Alder the tide was

at the low-water mark. Witness said the measurements were agreed to by a representative

of the owners of the Lady Cavan. Witness was able to give exactly the

position of the anchor light after it was hoisted.

Lord Justice Andrews – How exactly is the lamp secured in position?

– On a block with a stay.

Continuing, Mr. Torrens said that at low water mark half of the

mast and 6 feet of the funnel were visible. It was clear that the lights were

burning when the Alder sank, as the wicks were up in the burners, in

ordinary conditions, apart from fog, the light would be visible for about

a mile. The stern light was screened. Witness was with Mr. Reside on the 15th

June to take soundings, and also sailed over the course with him.

Cross-examined by Mr. MacDermott – Looking at the ship’s bow, would

one see the mast-head light a little to the left and above the anchor light?

– Yes, that is correct.

Would it be possible to see the mast head light and the stern light at

the same time in a fog? – It would be possible.

To Mr. Murphy – The actual stern light was the one produced.

The Court then adjourned for luncheon.

Wm. John Press, partner in the firm of James Maxton & Co.,

Ltd., naval architects and consulting engineers, proved a sketch showing

the beam of the lights on the Alder. The mast head light was 20 points

and the other 12 points.

Cross- examined by Mr. Chambers – Did you yourself see the point

of impact between these two vessels? – On the Lady Cavan, not the Alder.

The Alder is so designed to have no belting? – I cannot say, as I

have not seen it.

Did you make any calculation taking into account the damage done to the

vessel by the speed at the point of impact? – No, as I think that would be

impossible.

Did you examine the Alder at all? – I received reports from the

diver.

From the information did you form any conclusion that there was very low

penetration? - Yes.

In what condition was , the bow of the Lady Cavan?

– Very good, except for marks and scrapes.

You were able to form what speed there was at the impact? – I cannot say

what speed.

Did the marks on the Lady Cavan indicate the depth of

penetration? – Twenty feet on the port side.

Mr. Murphy – That gave you some indication of the impact? – Yes.

Michael O’Neill, aged 23, one of the survivors of the Alder,

stated that he was mate on the Alder at the time. He held a home trade

mate certificate, which he received in November last. The Alder had

a crew of 8 all told. The watch consisted of two on deck and two below. On

the 3rd April last they sailed from

Lord Justice Andrews – They both answer to their names, and have

whistling and bell sounds? – Yes.

Witness said that the captain was on the bridge when they got to the Whistling

Buoy. Witness called for the captain as he had been told to do, and he came

on deck at 3am. At the Whistling Buoy they became aware of the presence of

another boat at anchor, and he saw the anchor lights and heard the bell. They

found that it was the Lady Cavan. They exchanged signals with her,

and she indicated where the whistling Buoy was.

After passing the Whistling Buoy the weather cleared and they proceeded

towards the entrance to the Lough. They entered the Buoy Channel. Witness was

at the wheel. They passed the Hawlbowline Lighthouse about 3.45am. Coming up

the channel to the Hawlbowline Lighthouse the visibility was clear.

Lord Justice Andrews – Was that bout the point when you changed

your course? – Yes.

REDUCED TO SLOW

Proceeding, witness said they

later reduced to ‘slow’ and continued. Witness and Cahoun went forward.

They let down the anchor at 4.5am. with 30 fathom

lengths of chain. It was a very calm night. After he let down the anchor he

rang the bell. As it was a calm night the bell should be heard at a distance

of about a mile. After witness rang the bell he saw

Lord Justice Andrews –

Was the tide not strong to make her head down the channel? – The tide was

not strong.

Continuing witness said he

rang the bell again.

Lord Justice Andrews –

What time did you continue to ring it? – About a few seconds.

Resuming his evidence, O’Neill

said he rang the bell a third time. The first witness saw of the Lady Cavan

was when he noticed the two mast head lights and the two sidelights. As compared

with their ship, the Lady Cavan would be on the port side. The Lady

Cavan would then be about 500 feet away. Witness said he could see her

red and green lights. He heard a signal, one sharp blast from the Lady

Cavan. They heard no signal from her previous to that. ‘The Lady Cavan

appeared to be coming head-on for us’ proceeded the

witness. The Lady Cavan seemed to be altering to starboard. He next

heard someone on the Alder shout to the Lady Cavan: ’Go astern,’

and someone on the Lady Cavan answered: ‘Wee are going astern.’ The

Lady Cavan did not continue to go to starboard and came back again.

The Lady Cavan struck their boat about the middle of the after-hatch

on the port side. It was pretty heavy blow, and the witness thought she would

doing about 4 or 5 miles an hour, when she struck them.

After the Lady Cavan

struck them their boat (the Alder) listed to starboard.

Lord Justice Andrews –

Were the two boats interlocked after the collision? –No.

Lord Justice Andrews –

What did you think made her heel to starboard? – The blow.

THREW A LINE

Immediately after the collision witness proceeded the Lady Cavan

backed out from them again. The Lady Cavan threw the Alder a

line. After the collision witness could not see the Alder swinging.

He tried to get a lifeboat out but was unable to do so. He tried to get out

on the port side, but she heeled over on the port side. The Alder sank

within about four minutes from the time she was hit by the Lady Cavan.

All hands were on deck at the time of the collision. The captain’s wife was

also on deck. Cahoun,

Cross-examines by Mr. MacDermott – You say that at the time of the

collision all hands were on deck? – Yes.

The time you let go the anchor who was with you?

– The skipper, Cahoun and myself.

No other person before that? – Not that I know of.

Was

You remember the night you came to the Whistling Buoy and you hailed the

Lady Cavan? – No, she hailed us.

At the time she hailed you could you have been bound for

At the time you saw the Lady Cavan you had not seen the Whistling

Buoy? – No.

How far were you away from the Whistling Buoy when the Lady Cavan

hailed you? – I cannot exactly say.

Did you whistle passing the Lady Cavan? – No.

How long was it after you left the Whistling Buoy before the weather

began to clear? – Scarcely five minutes.

Did I gather from your evidence that you had good visibility down to No.

6 buoy? – Yes.

Did you vary your speed passing the Lighthouse? – No.

Were you able to see the lights on Greenore? – No.

All you had to navigate by were lights? – That was all.

What time did you say it was when you dropped anchor? – Approximately

4.5am.

Are you a bit confused about your time regarding this? - No.

Did you tell the Master of the Lady Cavan that you were ten or

fifteen minutes anchored before the collision? – No.

Would you swear to that? – I would.

If there was any vessel close after you from the Whistling Buoy would

the stern light of your ship be visible? – Oh yes.

Mr. MacDermott then turned to the body of the Court and asked a

man named Millar to stand up, and pointing towards him, he asked the

witness –

Had you any conversation with this man on the Lady Cavan? – Yes.

Did you say anything to him about the time you had been anchored? – No.

Where had you the conversation? – With Mr. Millar on the deck.

Continuing, witness said they were anchored about five minutes before

the collision took place. There was no doubt that the anchor light was showing

at the time.

Mr. MacDermott – Why did you not take the masthead light down? –

We looked around for other lights.

I suggest to you that you thought that you were satisfied that there was

no other ships coming down on you and that you might as well let it stay there

until you moved off again? – No, no.

To Mr. Black – There was nothing suggested to him about the conversation

with the Master when at the

The hearing was adjourned until 11 o’clock on Tuesday morning.

TUESDAY’S HEARING

James Hollywood said he had been ten years in the Coastal Service. Previous

to joining the Alder witness said he had been on the ss. Pine

for six months. He was a lamp trimmer. He was called about 3.45a.m. and got on deck shortly after4 o’clock. There was a thick fog,

and the boat was stopped. The anchor was let go as he went on deck. Witness

lit a candle and got the anchor light out of its position and lit it. He carried

it to the forecastle head. While he was hoisting the light he saw O’Neill

who was ringing the bell. Witness saw Cahoun. He was` leaving the forecastle

head to take in the side lights. Witness had the anchor light in position,

and was looking around to see if he could notice anything. He saw two masthead

lights and the port light of a boat, the Lady Cavan. It was heading

to the port side of the Alder, and was about 500 feet away from the

Alder. When he first saw it witness did not see or hear anything from

the Lady Cavan, but as she was coming towards them he heard one short

blast of her siren. That was the only signal he heard from the ship. The Lady

Cavan seemed to alter her course to starboard and straighten up again.

Witness heard someone shout on the Alder ‘Go astern’ and a reply came

form the Lady Cavan, ‘We are going astern’. After the collision the

Alder heeled over to starboard. The Alder sank in about 3 or

4 minutes after the collision. The crew were thrown into the water, and witness

was one of the three picked up.

Cross-examined by Mr. MacDermot, witness said he

did not hear any person being told to bring in the stern light. He agreed that

the wrong lights would mislead.

Wm. Cahoun seaman on the Alder said he had about 4 years

experience. His watch on this day was from 12 midnight to 4a.m. The mate was

also on watch. Sometime during that period witness called the master, and

towards the end of the watch went down to call the next watch. That was about

3.45a.m. and

After that witness went back on deck and when the time came to let go the

anchor the witness went forward to the forecastle, O’Neill going also,

witness took the stoppers off the port anchor and the anchor was let down.

That was shortly after 4 o’clock. Witness then went down to the bridge to

take in the side lights and noticed

To his Lordship – The Lady Cavan never appeared to slow down

at all.

Cross-examined by Mr. MacDermot- It was clear that

night that there were clear patches and very bad patches of fog? – It cleared

up after we left the buoy. The weather was bad when we anchored.

The masthead light should have been taken down, and also the rear light?

- Yes

You must have known that you were anchored in the channel? - I did not

know.

You passed No. 10 buoy?-I did not know whether we had or not.

Are you quite sure? - I saw the anchor being got ready

When you saw `lights did you know that they were lights of a vessel? - I

did.

If that vessel has stayed where she was without going to port side,

would she have cleared you? - I think she would.

Mr. Justice Andrews- In

In further cross-examination, witness agreed that when anchored in fog

it was essential to get the proper lights up at once.

Mrs. Madeline McGrath, widow of Wm. Robert McGrath, who was chief engineer

on the Alder, said her husband was 49 years of age. She could not say

what her husband’s weekly wage would be.

Mr. Black said the deceased’s earnings were April, 1934 to April 1935, £166 14s

6d; from April 1935 to April 1936, £222 13s 6d and from April 1936 to April

1937, £232 1s.

Mrs. McGrath continuing

her evidence said that out of her husband’s wages

she received £2 1s per week. Out of that she paid the rent and kept the house.

When the ship was laid up he was on a smaller wage and paid her 35s per week.

Witness had three children.

The eldest named Beatrice

Gwendoline, who

was 19 years of age. She had not been working since her father’s death. Prior

to that she worked in a mill in Bessbrook and received 17/4 per week. She

had to pay for stamps out of that. Witness’s second girl, Muriel

Elizabeth, was

12 years old and was still at school. Her son Allan

was 7 years old and was still at school. Her husband on the last occasion, had been nearly three years with Messrs. Fisher, and before that he was employed by Messrs.